Country Profiles

SYRIA

Basic Data

HEADS OF STATE WITH

A MILITARY BACKGROUND

A MILITARY BACKGROUND

7 of 13

(as of 2020)

Excluding interim/acting

appointments

Excluding interim/acting

appointments

Index Results

Scores on a scale of 1–5

Context

Syria’s legacy of actively waging or preparing for war has focused civil-military relations on loyalty to the ruling Arab Socialist Renaissance Party (the Ba'ath party), centralized presidential control, and reliance on external support. Syria has been in a declared state of war with Israel since 1948, it deployed large numbers of troops and intelligence assets to Lebanon in 1976–2005, and it has experienced civil war and foreign military interventions by both state and nonstate actors since 2011. The presence of Turkish-backed armed opposition groups in the north, the Syrian Democratic Forces with autonomous administration in the northeast, various extremist groups in the northwest, and residual fighters from the self-proclaimed Islamic State also exerts substantial influence on Syrian defense affairs.

In government controlled areas, the centrality of the Syrian Army and Armed Forces (SAAF) in public life is evident in the organic, formal relationship between the ruling Ba'ath party and the armed forces. In his dual capacity as commander in chief and party leader, the president controls the SAAF. Party commissars ensure loyalty within the military chain of command, and all military officers undergo training in Ba'ath ideology. In addition, the government has used the permanent war footing to justify the suppression of political freedoms, the opacity of the defense budget, and the militarization of society in the name of national security.

Syria’s relative lack of natural resources has resulted in longstanding dependence on Russia as a supplier of military equipment and weapons systems, with associated training. Since the early 1980s, Syria has maintained an alliance with Iran and its proxy, the Lebanese organization Hezbollah. These external actors have impacted Syrian defense affairs by deploying troops and military advisors in the country, creating loyalist militias, and cultivating their own networks within government forces during the ongoing civil war.

In government controlled areas, the centrality of the Syrian Army and Armed Forces (SAAF) in public life is evident in the organic, formal relationship between the ruling Ba'ath party and the armed forces. In his dual capacity as commander in chief and party leader, the president controls the SAAF. Party commissars ensure loyalty within the military chain of command, and all military officers undergo training in Ba'ath ideology. In addition, the government has used the permanent war footing to justify the suppression of political freedoms, the opacity of the defense budget, and the militarization of society in the name of national security.

Syria’s relative lack of natural resources has resulted in longstanding dependence on Russia as a supplier of military equipment and weapons systems, with associated training. Since the early 1980s, Syria has maintained an alliance with Iran and its proxy, the Lebanese organization Hezbollah. These external actors have impacted Syrian defense affairs by deploying troops and military advisors in the country, creating loyalist militias, and cultivating their own networks within government forces during the ongoing civil war.

Key Points

- Syrian civil-military relations center on the relationship between the presidency and the armed forces, combining formal powers with informal modes of management.

- The armed forces’ central role in the ruling political order ensures their obedience to the executive, but heightens the importance of political and communal loyalty.

- Ba'ath party rule; the presence of powerful nonstate military actors; and the salience of sectarian, ethnic, and clan identity undermine the SAAF’s contributions to nation building.

- Civilian authorities have no role in developing and monitoring implementation of the defense budget, and only a limited role in approving it, along with no role in improving cost-effectiveness in the defense sector.

- Informal networks, parallel reporting structures, and minimal defense planning capacity reduce policy coherence, impede military readiness and effectiveness, and produce suboptimal national defense outcomes.

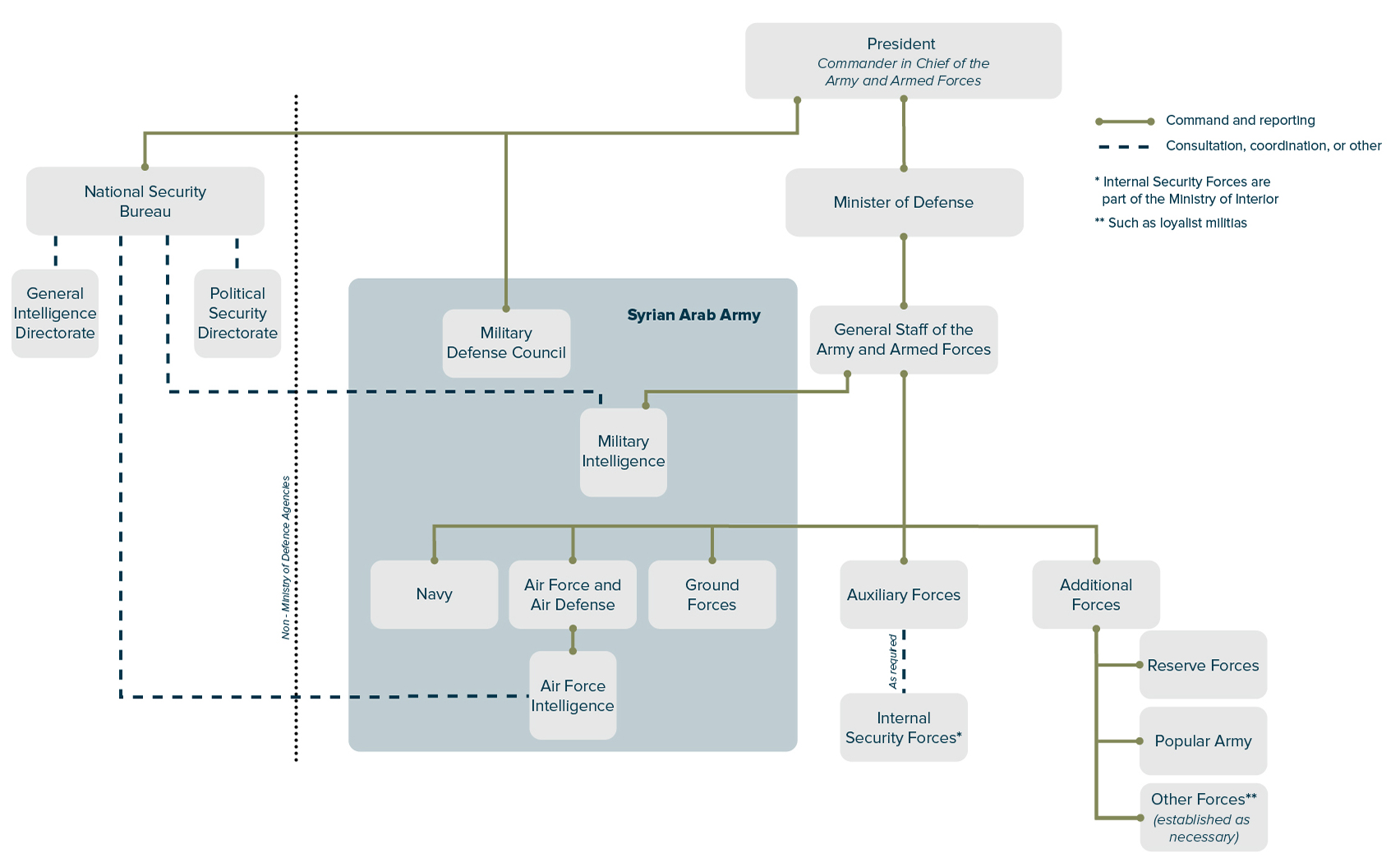

Institutional Stability

The constitution does not privilege the armed forces in any way, simply stating their mission as “defending the nation’s territory and sovereignty, serving the interests of the Syrian people, [and] protecting their goals and national security.” As a state institution headed by a cabinet minister, the SAAF falls nominally under government authority, but in practice and in law the president of the republic exercises effective command and control. He is the principal source of defense-related legislation, with power to declare war, announce a general mobilization, sign peace treaties, declare a state of emergency, and make senior command appointments. The president also makes key defense policy decisions on military deployments, arms purchases, promotions and transfers, demobilizations, and rules of engagement, with input from the Military Defense Council that he heads, just as the National Security Office plays an important role in coordinating the role of intelligence agencies.

Civilian authorities are marginal in defense affairs. Parliament approves the defense budget, but only as a single line item, and neither the Ministry of Finance nor public auditing agencies are empowered to examine it. Neither the parliamentary National Security Committee nor any of its members dare question defense officials, and the defense minister, who is always an army officer, acts as a representative of the president rather than of the government.

The minister of defense and other senior security officials mediate the command relationship between the president and the SAAF. The president’s role as secretary-general of the Ba'ath party complements this relationship. The Political Directorate of the Ministry of Defense implants party ideology throughout internal publications and maintains branches in all military units down to company level. Party ideology is prominent in military education. This party structure frames coordination with internal security and law enforcement agencies, which are sometimes designated as “auxiliary forces” to the SAAF.

SAAF Command has formal control over the regular army, but generally lacks effective control over the numerous loyalist militias that have emerged in the course of the civil war, even though legally these are “additional forces” under its nominal authority. Instead, the president wields overarching military and security authority. He exercises overriding control through a special military office attached to the presidency and through informal, parallel networks within the SAAF.

Russia and Iran have also exerted considerable influence over the defense sector since the start of the civil war. They exercise direct administrative and operational control over a number of pro-government militias, including some that have been reorganized into formations nominally under SAAF Command. The existence of the autonomous Syrian Democratic Forces and of Turkish-backed anti-government armed groups further fragments and contests the provision of security by the central government.

The structure of authority centered on the president and the Ba'ath party excludes civilian agencies from playing a role in defense affairs, but also ensures that the SAAF’s only policymaking role is in the defense domain. The SAAF has played a command role in public order missions in the ongoing civil war, during which military courts have exercised extensive jurisdiction over civilians. The SAAF has otherwise avoided involvement in tasks that lie within the Ministry of Interior’s jurisdiction.

Key Legal Documents

- Legislative Decree 18 of 2003, last amended by Legislative Decree 15 of 2019, on military service including the role of the defense council

- Legislative Decree 61 of 1950, last amended by Law No. 13 of 2016, on military penal code and court procedures

- Legislative Decree 104 of 2011, on the mobilization of society and the armed forces for war

Civilian authorities are marginal in defense affairs. Parliament approves the defense budget, but only as a single line item, and neither the Ministry of Finance nor public auditing agencies are empowered to examine it. Neither the parliamentary National Security Committee nor any of its members dare question defense officials, and the defense minister, who is always an army officer, acts as a representative of the president rather than of the government.

The minister of defense and other senior security officials mediate the command relationship between the president and the SAAF. The president’s role as secretary-general of the Ba'ath party complements this relationship. The Political Directorate of the Ministry of Defense implants party ideology throughout internal publications and maintains branches in all military units down to company level. Party ideology is prominent in military education. This party structure frames coordination with internal security and law enforcement agencies, which are sometimes designated as “auxiliary forces” to the SAAF.

SAAF Command has formal control over the regular army, but generally lacks effective control over the numerous loyalist militias that have emerged in the course of the civil war, even though legally these are “additional forces” under its nominal authority. Instead, the president wields overarching military and security authority. He exercises overriding control through a special military office attached to the presidency and through informal, parallel networks within the SAAF.

Russia and Iran have also exerted considerable influence over the defense sector since the start of the civil war. They exercise direct administrative and operational control over a number of pro-government militias, including some that have been reorganized into formations nominally under SAAF Command. The existence of the autonomous Syrian Democratic Forces and of Turkish-backed anti-government armed groups further fragments and contests the provision of security by the central government.

The structure of authority centered on the president and the Ba'ath party excludes civilian agencies from playing a role in defense affairs, but also ensures that the SAAF’s only policymaking role is in the defense domain. The SAAF has played a command role in public order missions in the ongoing civil war, during which military courts have exercised extensive jurisdiction over civilians. The SAAF has otherwise avoided involvement in tasks that lie within the Ministry of Interior’s jurisdiction.

Political System

Contested Control over the Defense Sector

Russian and Iranian military assistance has staved off the collapse of president Bashar al-Assad’s ruling order and the regular armed forces since 2012. However, this has left the government with contested sovereign control over its own defense sector and the Syrian battle space. This is demonstrated by the agreements Russia has reached independently with Israel, the United States, and Turkey, governing military operations and deconfliction in Syria.

Russia initially supplied weapons and training, but in 2015 it intervened directly in Syria and embedded advisors in Syrian army units down to battalion level. Since then, Russia has focused mainly on retraining, reequipping, and rehabilitating the regular army. It has also integrated former opposition fighters into loyalist units that are nominally under SAF control, but in reality commanded by Russian officers.

Starting in 2012, Iran assisted in the revision of government strategy, formed loyalist Syrian militias, and deployed Lebanese Hezbollah forces and foreign Shia militias, backed by Iranian military advisors and specialists. It has mostly invested in building these militias, but also sought influence with key regime figures such as the president’s brother Maher, who commands the 4th Division.

Russia and Iran neither coordinate their military assistance with each other nor channel it through the Ministry of Defense and SAF. Instead, they maintain separate command and control structures. As a result, forces allied to the Syrian government, Russia, and Iran do not constitute an integrated defense sector. These forces diverge over military strategy, vie for influence within the regular army—reflected in frequent shuffling of senior officers—and sometimes compete for control of economic facilities and assets. The government is unable to fund Russian- or Iranian-backed militias and army units, compelling it to rely on forces it does not control.

Russia initially supplied weapons and training, but in 2015 it intervened directly in Syria and embedded advisors in Syrian army units down to battalion level. Since then, Russia has focused mainly on retraining, reequipping, and rehabilitating the regular army. It has also integrated former opposition fighters into loyalist units that are nominally under SAF control, but in reality commanded by Russian officers.

Starting in 2012, Iran assisted in the revision of government strategy, formed loyalist Syrian militias, and deployed Lebanese Hezbollah forces and foreign Shia militias, backed by Iranian military advisors and specialists. It has mostly invested in building these militias, but also sought influence with key regime figures such as the president’s brother Maher, who commands the 4th Division.

Russia and Iran neither coordinate their military assistance with each other nor channel it through the Ministry of Defense and SAF. Instead, they maintain separate command and control structures. As a result, forces allied to the Syrian government, Russia, and Iran do not constitute an integrated defense sector. These forces diverge over military strategy, vie for influence within the regular army—reflected in frequent shuffling of senior officers—and sometimes compete for control of economic facilities and assets. The government is unable to fund Russian- or Iranian-backed militias and army units, compelling it to rely on forces it does not control.

An estimated 90 percent of career military personnel belong to the Alawi community, an offshoot of Shia Islam. The officer corps is factionalized along communal and personal loyalty lines, resulting in informal networks that bypass formal command structures. Russian and Iranian influence adds complexity to these dynamics. The salience of communal identities and clan ties accounts for the SAAF’s cohesion and enduring obedience to presidential orders.

The SAAF’s survival is integral to the survival of the political order, with the president at its apex. Civilian political actors outside the Ba'ath party cannot penetrate the SAAF, and the SAAF does not intervene in politics. This explains how the SAAF has coexisted with pro-government militias that do not fall under its effective control, even though these militias constitute “additional” forces legally under its command. The continuing challenge posed by autonomous and anti-government armed groups to the ruling political order reinforces the need to maintain an integral relationship with the military as the principal means of dominating national politics.

Military culture does not inculcate subordination to civilian authority or the rule of law, nor does it emphasize values of citizen’s rights or political pluralism. The SAAF does not deliver public goods or services outside its defense remit, and officers are rarely rewarded with appointments in the civilian state bureaucracy after retirement. A small number of retirees hold important positions in local government, based on security or social considerations, perpetuating presidential power rather than extending the military’s institutional influence.

SAAF Social Media Engagement

Twitter

Twitter

Tweets

4,512

4,512

Followers

16,739

16,739

Listed

106

106

Facebook

Facebook

Likes

337,933

337,933

Followers

413,675

413,675

Talked About

122,426

122,426

Youtube

Youtube

Uploads

438

438

Video Views

3,870,302

3,870,302

Perceptions of the military contrast sharply across Syrian society. Large portions of the population see it as politically partisan, but others, especially in the Alawi community, regard it as upholding national sovereignty. The military sees its defense of the ruling political order as integral to serving the state and embodying national identity. The SAAF does not restrict public debate, except in defense affairs, but loyalist social media have complained openly of perceived failings and unpopular measures by the Ministry of Defense and SAAF commanders.

Nation Building and Citizenship

Syria Hybrid Defense Sector

Attrition in personnel between 2011 and 2013 prompted the formation of local militias loyal to the governing political order, and led to the utilization of non-Syrian Shiite militias supported by Iran. The most important Syrian loyalist militia was the National Defense Forces, comprising a number of brigades and battalions with a total strength of 60,000 at their height. Other local militias include the Baath Battalions, drawn from the ranks of the ruling Baath party, and the Desert Hawks and Eagles of the Whirlwind.

Russia sought to reverse this situation following its intervention in September 2015, by incorporating prominent militias into the official Syrian military. To this end, it established new army units, including the 4th Corps (2015) and 5th Corps (2016). The Baath Battalions formed the nucleus of the 5th Corps, for example.

The incorporation of former opposition fighters into the ranks of these new army corps reduced Iranian influence, prompting Iran to establish the new Local Defense Forces militia. To imbue them with legal status, Iran obtained a presidential decree attaching the Local Defense Forces to the General Command of the Armed Forces on an open-ended basis, "until the end of the crisis."

The lack of transparency makes it impossible to know the exact strength of loyalist militias, but it is estimated that approximately 140,000 individuals belong to militias loyal to Russia or Iran.

No legislation specifically regulates loyalist militias, but the 2003 Military Service Law legitimizes the establishment of "other forces when necessary" under the legal designation of "additional forces." However, a large portion of the militias currently operating in Syria remain outside the actual control of the military. The government also lacks the means to disarm, reintegrate, or employ former fighters, forcing it to permit militias to retain their ties to Russia or Iran. This negatively affects efforts to stabilize local communities, increases the risk of continued armed conflict, and reduces opportunities to reform the defense sector and professionalize the armed forces.

Russia sought to reverse this situation following its intervention in September 2015, by incorporating prominent militias into the official Syrian military. To this end, it established new army units, including the 4th Corps (2015) and 5th Corps (2016). The Baath Battalions formed the nucleus of the 5th Corps, for example.

The incorporation of former opposition fighters into the ranks of these new army corps reduced Iranian influence, prompting Iran to establish the new Local Defense Forces militia. To imbue them with legal status, Iran obtained a presidential decree attaching the Local Defense Forces to the General Command of the Armed Forces on an open-ended basis, "until the end of the crisis."

The lack of transparency makes it impossible to know the exact strength of loyalist militias, but it is estimated that approximately 140,000 individuals belong to militias loyal to Russia or Iran.

No legislation specifically regulates loyalist militias, but the 2003 Military Service Law legitimizes the establishment of "other forces when necessary" under the legal designation of "additional forces." However, a large portion of the militias currently operating in Syria remain outside the actual control of the military. The government also lacks the means to disarm, reintegrate, or employ former fighters, forcing it to permit militias to retain their ties to Russia or Iran. This negatively affects efforts to stabilize local communities, increases the risk of continued armed conflict, and reduces opportunities to reform the defense sector and professionalize the armed forces.

Prior to 2011, such activities as paramilitary training for high school and university students anchored nation building, but the militarization of politics and society has weakened the sense of shared national purpose since then. A large part of the population no longer feels it owes allegiance to the central state or the military, as demonstrated by refugees’ reluctance to return, tenuous government control in recaptured areas, and survival or resurgence of armed opposition groups in parts of the country.

Patterns of recruitment and assignment in the career armed forces have long revolved around confessional, ethnic, regional, clan, and class identities. Alawis head most key commands and combat units, a trend that began under former president Hafez al-Assad (1970–2000). Preferential admittance to military academies and patronage networks within the SAAF have intensified the militarization of the Alawi community. Informal quotas exist for non-Alawi communities and regions, and Sunni Muslims tend to be assigned to support services or nonessential combat units as they rise in the ranks.

Alawis identify closely with the military, but many other Syrians see the military as sectarian, partisan, and corrupt. Even Alawis recognize that military careers and material entitlements depend on favoritism and political connections. The SAAF profiles population groups according to their perceived loyalty, in line with the general outlook of the ruling political order. SAAF units enjoyed good community relations until 2011, but the military now recruits more heavily among Alawis, and draws on select Sunni clans in the north and east to form ad hoc units. Profiling has been evident in the use of indiscriminate firepower and chemical weapons in specific localities.

The SAAF recruits women, and does not discriminate between male and female personnel with regard to pay and pensions. A military academy for women has an annual intake of 70‒100 cadets, and increased recruitment during the ongoing civil war has swollen the number of women in the SAAF to some 8,500, including in combat units assigned to garrison roles. Female personnel face no formal impediments to promotion, but the military does not open up avenues for career advancement, promotion, or diversification of military specialties for women. SAAF regulations allow for maternity leave and flexible working hours for women, but the military penal code does not address sexual discrimination or harassment.

The military does not engage in large-scale public media or outreach, nor does it have a civil-military cooperation program. It leaves all related activities, including the provision of medical services, development assistance, and rehabilitation and reconstruction in the context of the ongoing civil war, entirely to civilian government agencies.

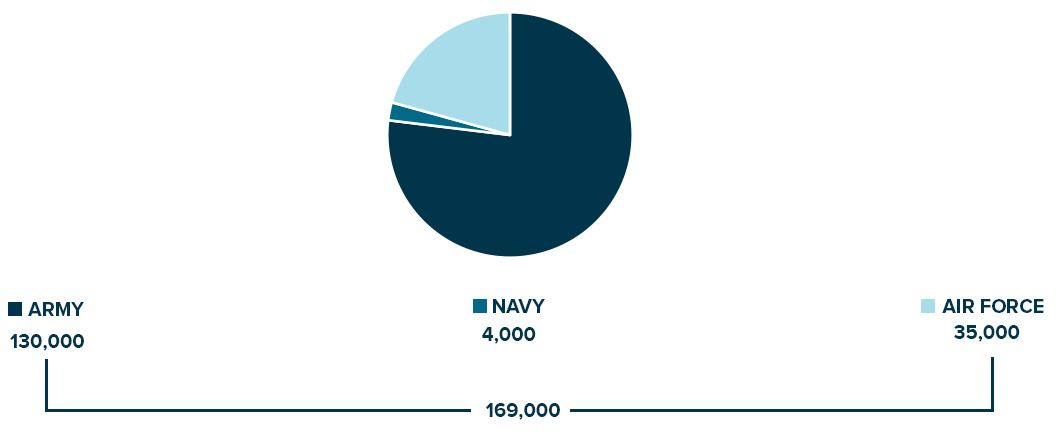

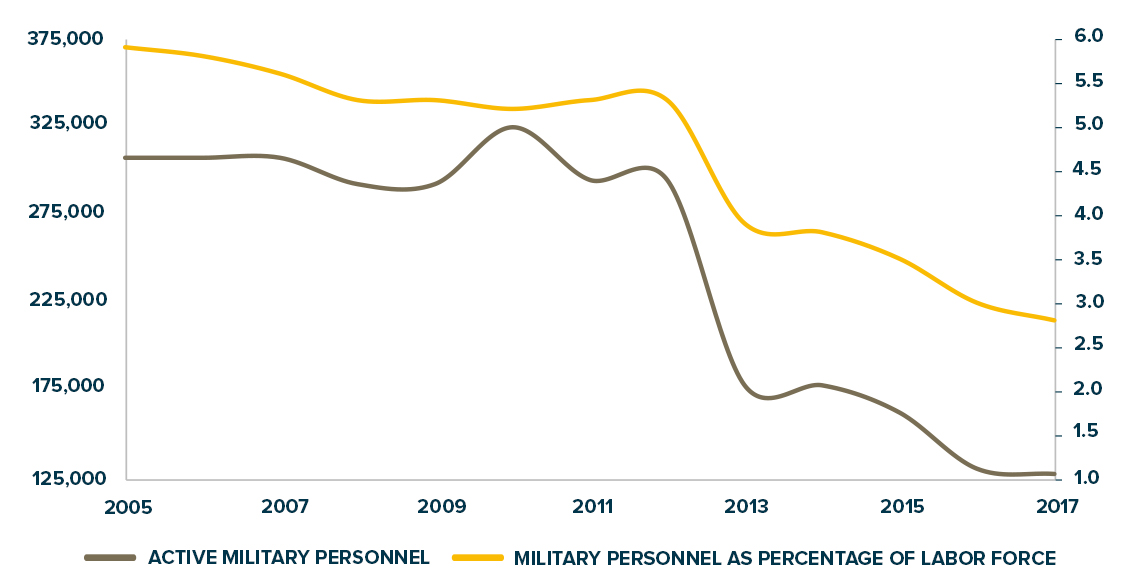

Active Military Personnel Versus Labor Force

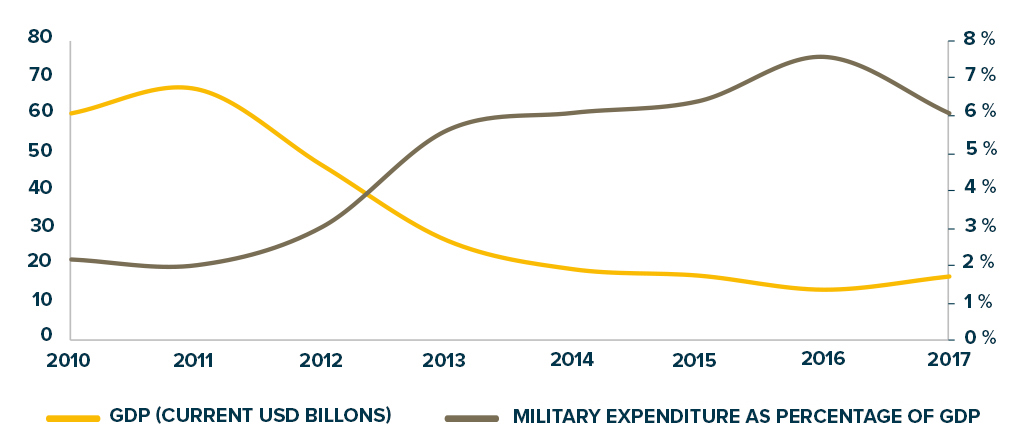

Budget and Economy

Civilian authorities have no role in developing or monitoring implementation of the defense budget, and only a limited role in approving it. The Ministry of Defense prepares a budget reflecting the needs of all bodies under its jurisdiction, with input from the SAAF. The Council of Ministers and Parliament approve this budget as a single line item, without access to its details. Civilian authorities do not have access to details of foreign military assistance to Syria, although debt repayments are known to have been charged to the general state budget. Only the president, as commander in chief, has the power to approve and amend the budget, make new allocations, or exercise oversight.

Actual defense spending has deviated from the approved budgets because of combat needs, fluctuating exchange rates, and increases in military salaries and pensions during the ongoing civil war. Russia and Iran bear some of these costs, but all costs, including foreign military debt, appear to be reflected in the official defense budget. External civilian agencies do not audit military accounts, except for the administrative budget of the Ministry of Defense, and the law prohibits public discussion of the defense budget. An internal military inspection panel monitors SAAF spending, and the Military Intelligence Section is informed of any audits or corruption.

The military is not known to control discretionary funds, but it manages several economic enterprises that provide construction, medical, and limited manufacturing and retail services. Their combined revenue is modest, and is reported in the defense budget. In contrast, the scale of illicit income generation is considerable. Officers invest in commercial projects, take bribes to award promotions and transfers, sell fuel and military materiel on the black market, and derive illegal earnings from protecting illegal trade and smuggling. These practices are longstanding, but the ongoing civil war has offered new opportunities for extortion at checkpoints, looting of private homes and enterprises, and ransom- and bribe-taking. Income-generating activities by loyalist militias, anti-government armed groups, and the autonomous administration in the northeast weaken government revenue and its ability to plan or enforce economic policies.

The military does not influence economic policymaking, nor is it known to lobby for or against specific policies. Military personnel or their families have complained publicly during the ongoing civil war about the inadequacy of pay, pensions, and compensation for death or injury. But this has not translated into open opposition among individual personnel or from the military to the government’s economic or social policies.

The military has not added significant value to the economy, apart from its contribution to domestic consumption, but has played a substantial role as an employer and a source of household survival. Social security and health insurance for military personnel are commensurate with those for the public sector, and generous in comparison to the private sector. A series of increases since 2011 has ensured that military pay and pensions have risen at a faster rate than those of the civil service, but increases have failed to keep up with the severe depreciation in purchasing power.

Actual defense spending has deviated from the approved budgets because of combat needs, fluctuating exchange rates, and increases in military salaries and pensions during the ongoing civil war. Russia and Iran bear some of these costs, but all costs, including foreign military debt, appear to be reflected in the official defense budget. External civilian agencies do not audit military accounts, except for the administrative budget of the Ministry of Defense, and the law prohibits public discussion of the defense budget. An internal military inspection panel monitors SAAF spending, and the Military Intelligence Section is informed of any audits or corruption.

The military is not known to control discretionary funds, but it manages several economic enterprises that provide construction, medical, and limited manufacturing and retail services. Their combined revenue is modest, and is reported in the defense budget. In contrast, the scale of illicit income generation is considerable. Officers invest in commercial projects, take bribes to award promotions and transfers, sell fuel and military materiel on the black market, and derive illegal earnings from protecting illegal trade and smuggling. These practices are longstanding, but the ongoing civil war has offered new opportunities for extortion at checkpoints, looting of private homes and enterprises, and ransom- and bribe-taking. Income-generating activities by loyalist militias, anti-government armed groups, and the autonomous administration in the northeast weaken government revenue and its ability to plan or enforce economic policies.

The military does not influence economic policymaking, nor is it known to lobby for or against specific policies. Military personnel or their families have complained publicly during the ongoing civil war about the inadequacy of pay, pensions, and compensation for death or injury. But this has not translated into open opposition among individual personnel or from the military to the government’s economic or social policies.

The military has not added significant value to the economy, apart from its contribution to domestic consumption, but has played a substantial role as an employer and a source of household survival. Social security and health insurance for military personnel are commensurate with those for the public sector, and generous in comparison to the private sector. A series of increases since 2011 has ensured that military pay and pensions have risen at a faster rate than those of the civil service, but increases have failed to keep up with the severe depreciation in purchasing power.

National Defense

The unambiguous subordination of the armed forces to the president facilitates decisionmaking, but the exclusion of the rest of the executive branch, the prevalence of informal networks and parallel reporting structures, and the minimal planning capacity of the Ministry of Defense greatly reduce policy coherence, impede military readiness and effectiveness, and produce suboptimal national defense outcomes. Extensive politicization of the armed forces exacerbates factionalism in the officer corps, further impeding professional development, distorting performance incentives, and undermining command and control. Extensive reliance on parallel networks and micromanagement of the defense sector further weaken the cohesion of the armed forces and block systemic monitoring and evaluation.

The SAAF has held together and achieved battlefield success on multiple fronts, despite these organizational challenges and losing two-thirds of its strength at the beginning of the civil war. It has also displayed low initiative, poor ability to conduct combined arms operations, and a general reluctance to undertake offensive actions. The SAAF has suffered heavy casualties due to poor training and inadequate gear, and equally heavy attrition of combat equipment due to poor maintenance and weak recovery and repair capabilities. It cannot deter frequent Israeli air attacks or the deployment of U.S. and Turkish troops across national territory, or prevent the reappearance of armed opposition in the south.

Management of the defense burden is inefficient. Defense spending has grown as state finances have contracted. The preference for maintaining a large military prior to 2011 precluded modernization, and maintaining political control during the subsequent war has frustrated lesson learning and cost-benefit assessments. The result is using firepower in ways that displaces populations and destroys vital infrastructure that the government needs to rebuild the country, and an inability to translate ad hoc tactical innovations such as mixed-unit task forces into doctrinal or structural adaptations.

SAAF structure is inefficient. The SAAF must coexist with numerous pro-government militias that come nominally under its command, but which are in fact controlled by other loyalist bodies, or by Russia and Iran. These allies shoulder the financial costs of militias they establish, but this leaves the Syrian government with a command and control problem and a future burden of demobilizing and reintegrating militiamen. Effective command and control relies on informal procedures. A special military office in the presidential palace routinely bypasses SAAF Command to direct deployments and operations.

Civilian authorities lack competences that could help manage defense resources and assist in developing capabilities. This deprives the military of potential expertise in strategic planning, lesson learning, military education, and technical and professional skills. The SAAF is unable to reduce human and material losses and mobilize resources, and the Ministry of Defense has been compelled to pledge that conscripts will serve in their home regions, to defuse opposition from local communities. Women mainly perform medical and clerical roles, and garrison or neighborhood protection roles. These limitations reflect an institutional mindset that minimizes absorption of foreign defense expertise and training.

The SAAF has held together and achieved battlefield success on multiple fronts, despite these organizational challenges and losing two-thirds of its strength at the beginning of the civil war. It has also displayed low initiative, poor ability to conduct combined arms operations, and a general reluctance to undertake offensive actions. The SAAF has suffered heavy casualties due to poor training and inadequate gear, and equally heavy attrition of combat equipment due to poor maintenance and weak recovery and repair capabilities. It cannot deter frequent Israeli air attacks or the deployment of U.S. and Turkish troops across national territory, or prevent the reappearance of armed opposition in the south.

Management of the defense burden is inefficient. Defense spending has grown as state finances have contracted. The preference for maintaining a large military prior to 2011 precluded modernization, and maintaining political control during the subsequent war has frustrated lesson learning and cost-benefit assessments. The result is using firepower in ways that displaces populations and destroys vital infrastructure that the government needs to rebuild the country, and an inability to translate ad hoc tactical innovations such as mixed-unit task forces into doctrinal or structural adaptations.

SAAF structure is inefficient. The SAAF must coexist with numerous pro-government militias that come nominally under its command, but which are in fact controlled by other loyalist bodies, or by Russia and Iran. These allies shoulder the financial costs of militias they establish, but this leaves the Syrian government with a command and control problem and a future burden of demobilizing and reintegrating militiamen. Effective command and control relies on informal procedures. A special military office in the presidential palace routinely bypasses SAAF Command to direct deployments and operations.

Civilian authorities lack competences that could help manage defense resources and assist in developing capabilities. This deprives the military of potential expertise in strategic planning, lesson learning, military education, and technical and professional skills. The SAAF is unable to reduce human and material losses and mobilize resources, and the Ministry of Defense has been compelled to pledge that conscripts will serve in their home regions, to defuse opposition from local communities. Women mainly perform medical and clerical roles, and garrison or neighborhood protection roles. These limitations reflect an institutional mindset that minimizes absorption of foreign defense expertise and training.

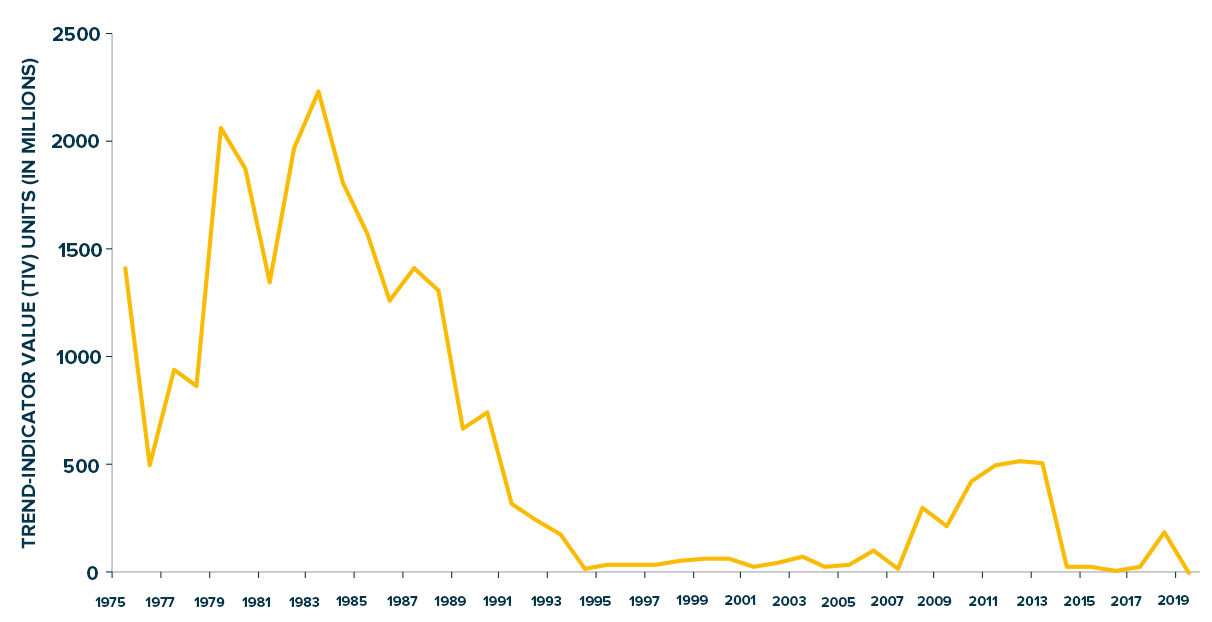

Arms Imports

Note: The TIV is a unit of measure developed by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) to calculate the volume of international transfers of major conventional weapons. It does not represent actual prices and cannot be directly compared with figures for GDP or military spending.

Source: SIPRI