Country Profiles

EGYPT

Basic Data

HEADS OF STATE WITH

A MILITARY BACKGROUND

A MILITARY BACKGROUND

7 of 8

(as of 2020)

Excluding interim/acting

appointments

Excluding interim/acting

appointments

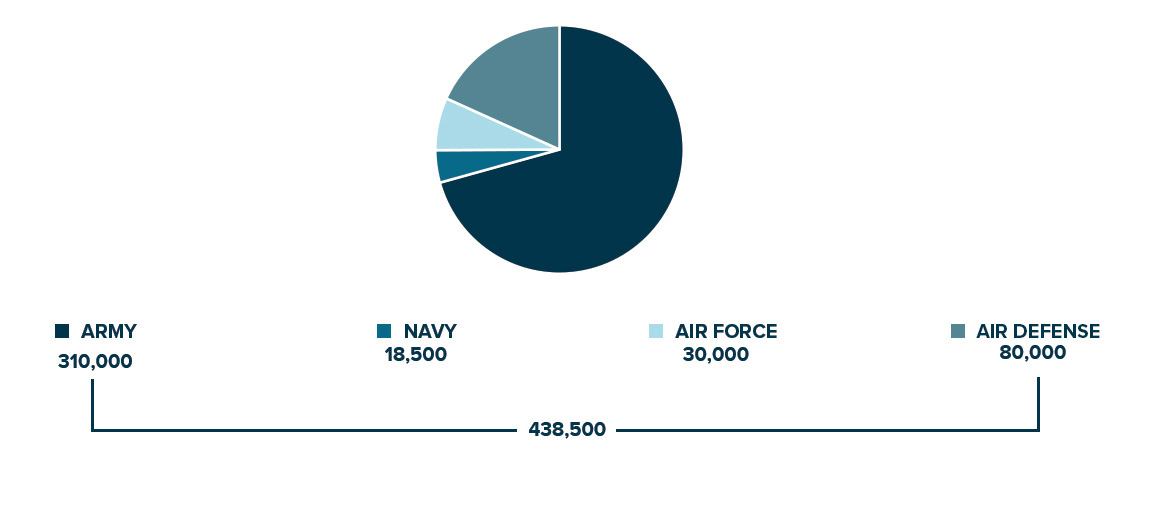

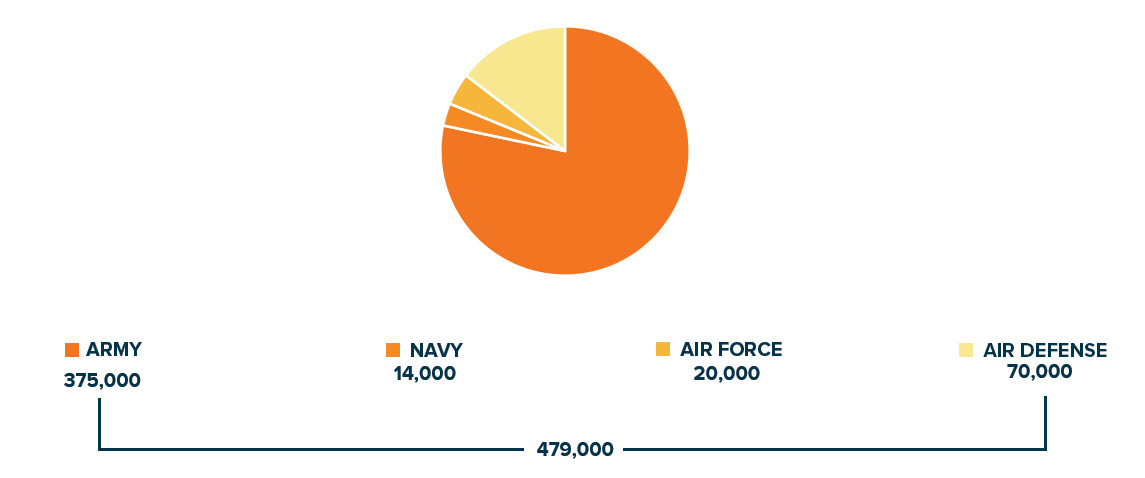

Total Military Personnel

ACTIVE

2020 Data | Source: International Institute for Strategic Studies

RESERVE

2020 Data | Source: International Institute for Strategic Studies

Index Results

Scores on a scale of 1–5

Context

The Egyptian Armed Forces (EAF) have had a profound effect on Egypt since the overthrow of the monarchy in 1952 and the creation of the republic in 1953. A state of war with Israel and military deployments to Syria (1958–1961) and Yemen (1963–1967) reinforced the salience of the armed forces in the early years, and EAF officers have held the presidency for all but two of the years since 1953. This has made the likelihood of genuine civilian control remote.

The EAF benefited from Soviet assistance during the Cold War, but became the second largest recipient of U.S. Foreign Military Financing after the 1979 peace with Israel, receiving $1.3 billion in all but two years since. Egypt’s military support for Iraq during its war with Iran (1980–1988) and for the coalition to liberate Kuwait (1990–1991) cemented the importance of the EAF to alliances with Gulf Cooperation Council member states and with the United States.

Egypt depends heavily on foreign assistance to meet defense needs, and it positions itself as an ally of the West in countering terrorism, opposing Iranian influence, and curbing illegal migration to Europe to ensure this support continues. Egypt nonetheless declined to deploy ground troops in support of the Saudi-led intervention in Yemen from 2015 onwards.

Egypt has, in contrast, provided military and intelligence assistance to the Libyan National Army faction in the Libyan civil war, and threatened to intervene directly in June 2020. The EAF has, however, struggled since 2011 to contain an armed insurgency in the Sinai Peninsula. Egypt has also implemented a multi-year effort to develop military infrastructure and acquire combat hardware to protect Red Sea shipping lanes and its Zuhr natural gas fields in the Mediterranean Sea.

The EAF benefited from Soviet assistance during the Cold War, but became the second largest recipient of U.S. Foreign Military Financing after the 1979 peace with Israel, receiving $1.3 billion in all but two years since. Egypt’s military support for Iraq during its war with Iran (1980–1988) and for the coalition to liberate Kuwait (1990–1991) cemented the importance of the EAF to alliances with Gulf Cooperation Council member states and with the United States.

Egypt depends heavily on foreign assistance to meet defense needs, and it positions itself as an ally of the West in countering terrorism, opposing Iranian influence, and curbing illegal migration to Europe to ensure this support continues. Egypt nonetheless declined to deploy ground troops in support of the Saudi-led intervention in Yemen from 2015 onwards.

Egypt has, in contrast, provided military and intelligence assistance to the Libyan National Army faction in the Libyan civil war, and threatened to intervene directly in June 2020. The EAF has, however, struggled since 2011 to contain an armed insurgency in the Sinai Peninsula. Egypt has also implemented a multi-year effort to develop military infrastructure and acquire combat hardware to protect Red Sea shipping lanes and its Zuhr natural gas fields in the Mediterranean Sea.

Key Points

- The military enjoys high levels of cohesion and autonomy from civilian control and oversight, weakening the effectiveness of other state institutions.

- The armed forces’ central role in maintaining the ruling political order and shaping the presidency has eliminated or marginalized political parties and social groupings that could play an effective role in governance.

- The armed forces are broadly representative of society and contribute to nation building, but block participatory citizenship by propagating a brand of nationalism that prioritizes state control over civic life.

- The lack of civilian oversight over defense funding and spending reduces the military’s efficacy and allows it to engage in income-generating activities of dubious commercial feasibility and little economic utility.

- The administration of President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has diversified sources of arms imports and upgraded military capabilities, but the ability of the armed forces to deliver effective battlefield performance remains questionable.

Institutional Stability

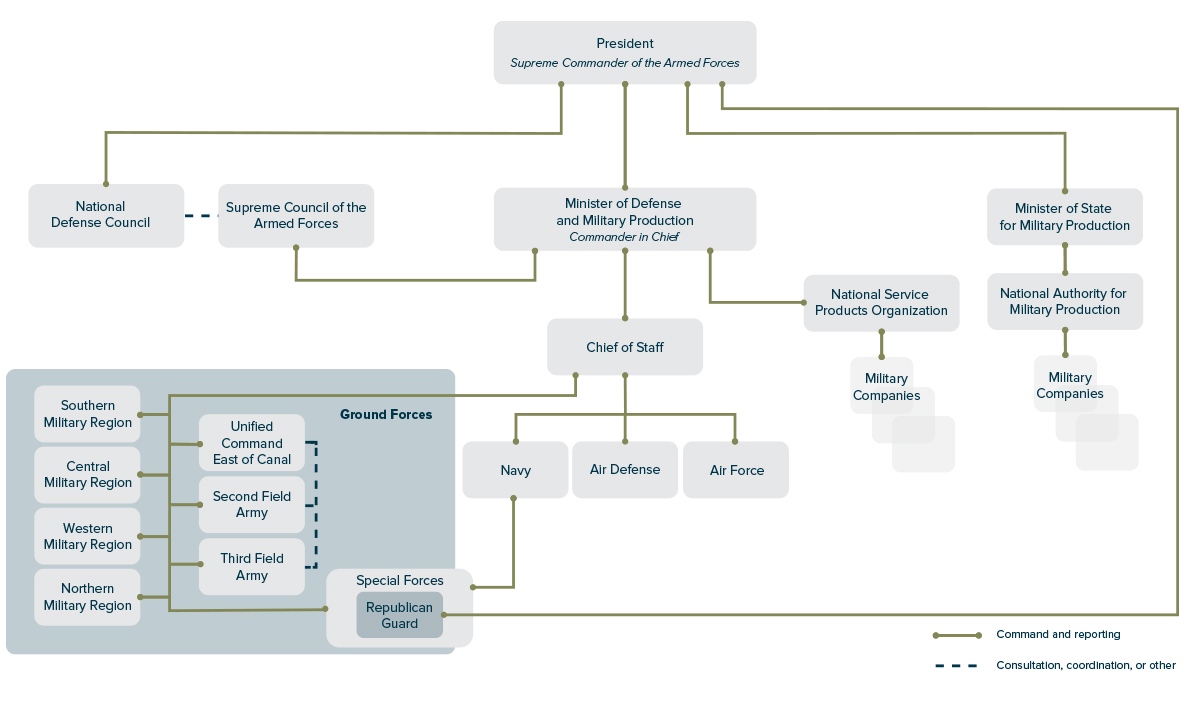

The amended constitution of 2019 grants the EAF the right to intervene in national politics and government at its own discretion, and effectively awards it supra-constitutional status, although the president has considerable formal and real power over defense affairs as head of state and supreme commander of the armed forces. The National Defense Council, which President Sisi reactivated in 2014 and which he heads, does not make consequential decisions. Instead, most important decisions result from an informal process involving the president, minister of defense, and key members of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, which according to a legal amendment in July 2020 may convene jointly with the National Security Council.

The prime minister, minister of finance, and parliamentary speaker are among the few civilian officials who attend National Defense Council meetings. They are privy to the outline of the defense budget, but neither they nor civilian bodies—including the legislature, public auditing agencies, and judiciary—have control or oversight functions over the budget, command appointments, or any other aspect or function of the armed forces.

The armed forces are not governed by a national defense law, so their relationship with the Council of Ministers and the president is shaped more by political and informal factors than by a legal framework. The president is the most powerful decisionmaker in defense affairs, but his ability to set overall defense policy and assign operational missions hinges heavily on securing the buy-in of senior military officers.

In accordance with the 2019 constitution, the minister of defense comes from the armed forces, but despite being commander in chief he is restricted by the need to appease sometimes contradictory pressures from the president and Supreme Council of the Armed Forces. The Ministry of Defense and the General Intelligence Directorate, which is heavily staffed by EAF officers, play lead roles in setting foreign policy, most notably in relation to Libya, Sudan, and the Palestinian Gaza Strip.

The military routinely delivers goods and services to the public, reflecting and exacerbating the shortcomings of civilian state agencies. The Ministry of Defense and other military entities also control significant extra-budgetary funds, disrupting government policies and skewing market dynamics. The hundreds of retired senior officers who occupy positions in the bureaucracy, local government, and public business sector often undermine the performance of these civilian state institutions.

The EAF undertakes public order missions, in part to redress perceived shortcomings in Ministry of Interior law enforcement and internal security agencies. Relations between the Ministries of Defense and Interior have historically been strained, but they currently observe a relatively clear division of labor in border security and counterterrorism.

The military justice system often encroaches on domains that normally come under civilian jurisdiction. The reimposition of an emergency law in April 2017 expanded the role of the armed forces in law enforcement while suspending judicial review, and in April 2020 a presidential amendment to the law in response to the coronavirus pandemic awarded military prosecutors the power to assist in public prosecution of crimes committed by civilians.

The prime minister, minister of finance, and parliamentary speaker are among the few civilian officials who attend National Defense Council meetings. They are privy to the outline of the defense budget, but neither they nor civilian bodies—including the legislature, public auditing agencies, and judiciary—have control or oversight functions over the budget, command appointments, or any other aspect or function of the armed forces.

Key Legal Documents

- Law 4 of 1968, last amended by Law 18 of 2014, on leadership and control over defense affairs and the armed forces

- Law No. 20 of 2014, establishing the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces

- Law 21 of 2014, establishing the National Defense Council

The armed forces are not governed by a national defense law, so their relationship with the Council of Ministers and the president is shaped more by political and informal factors than by a legal framework. The president is the most powerful decisionmaker in defense affairs, but his ability to set overall defense policy and assign operational missions hinges heavily on securing the buy-in of senior military officers.

In accordance with the 2019 constitution, the minister of defense comes from the armed forces, but despite being commander in chief he is restricted by the need to appease sometimes contradictory pressures from the president and Supreme Council of the Armed Forces. The Ministry of Defense and the General Intelligence Directorate, which is heavily staffed by EAF officers, play lead roles in setting foreign policy, most notably in relation to Libya, Sudan, and the Palestinian Gaza Strip.

The military routinely delivers goods and services to the public, reflecting and exacerbating the shortcomings of civilian state agencies. The Ministry of Defense and other military entities also control significant extra-budgetary funds, disrupting government policies and skewing market dynamics. The hundreds of retired senior officers who occupy positions in the bureaucracy, local government, and public business sector often undermine the performance of these civilian state institutions.

The EAF undertakes public order missions, in part to redress perceived shortcomings in Ministry of Interior law enforcement and internal security agencies. Relations between the Ministries of Defense and Interior have historically been strained, but they currently observe a relatively clear division of labor in border security and counterterrorism.

The military justice system often encroaches on domains that normally come under civilian jurisdiction. The reimposition of an emergency law in April 2017 expanded the role of the armed forces in law enforcement while suspending judicial review, and in April 2020 a presidential amendment to the law in response to the coronavirus pandemic awarded military prosecutors the power to assist in public prosecution of crimes committed by civilians.

Political System

Sinai Insurgency

The 1979 Camp David accords between Egypt and Israel led to the demilitarization of the Sinai Peninsula, limiting the ability of the Egyptian Armed Forces (EAF) to maintain control and facilitating smuggling and militant support to Gaza. Armed attacks on military and civilian targets by Sinai insurgents began after the 2011 protests that led to the ouster of then-president Hosni Mubarak. In 2015, fighters from the self-proclaimed Islamic State briefly occupied the town of Sheikh Zuweid and declared a short-lived “Sinai Province.” Hundreds of civilians, militants, and soldiers had died in violence by 2018, including 311 worshippers in the Rawda mosque attack in November 2017.

The EAF has employed a counterinsurgency strategy combining search-and-destroy missions with containment operations, such as checkpoints, barriers, curfews, and buffer zones along the Gaza border. Human rights organizations have reported on arbitrary arrests, unlawful home demolitions, and evictions of tens of thousands of residents. EAF counterinsurgency tactics have contained the insurgency to the Sinai Peninsula and prevented it from spreading to the Egyptian mainland, but not brought it to a definitive end. Operation Eagle in 2011 and Comprehensive Operation Sinai in 2018 both largely failed in their stated purpose of eradicating terrorism.

The EAF has not provided progress updates since March 2019, and its efforts are hampered by an absence of civilian oversight over national security policy formulation and execution, and lack of accountability when such policies fail. In 2020, militants claimed responsibility for dozens of attacks, in which over fifty soldiers and civilians were killed or wounded.

The EAF has employed a counterinsurgency strategy combining search-and-destroy missions with containment operations, such as checkpoints, barriers, curfews, and buffer zones along the Gaza border. Human rights organizations have reported on arbitrary arrests, unlawful home demolitions, and evictions of tens of thousands of residents. EAF counterinsurgency tactics have contained the insurgency to the Sinai Peninsula and prevented it from spreading to the Egyptian mainland, but not brought it to a definitive end. Operation Eagle in 2011 and Comprehensive Operation Sinai in 2018 both largely failed in their stated purpose of eradicating terrorism.

The EAF has not provided progress updates since March 2019, and its efforts are hampered by an absence of civilian oversight over national security policy formulation and execution, and lack of accountability when such policies fail. In 2020, militants claimed responsibility for dozens of attacks, in which over fifty soldiers and civilians were killed or wounded.

The EAF was a pillar of the ruling political order that emerged in 1953, and is the most powerful partner in the coalition of state institutions governing Egypt since 2013. The military is the senior partner in the division of labor with law enforcement and internal security agencies, but President Sisi’s heavy reliance on the EAF to govern has narrowed his political base and hollowed out the civilian apparatus of state.

The military has little visible interest in the formation of government or choice of ministers. The minister of defense does not exercise major or routine influence on government policies in nondefense spheres, except for foreign policy. Civilians in authority do not oppose the EAF, even if they privately consider its role detrimental. Sisi recognizes the potential threat posed by the armed forces and appoints military confidants to key positions, rotates senior EAF commanders frequently, and leverages his background as former head of Military Intelligence to keep officers in line.

Professional criteria are necessary for promotion in the EAF, subject to the premium placed on personal loyalty to the president and superior commanders. This loyalty scheme promises post-retirement appointments in government agencies or public sector companies to secure the obedience of officers during service. Cliques based on graduating class and military college influence command appointments. The EAF's corporate identity and cohesion prevent the establishment of parallel, state-sponsored armed organizations, and block foreign governments from wielding influence in its ranks.

EAF Social Media Engagement

Twitter

Twitter

Tweets

5,466

5,466

Followers

2,891,016

2,891,016

Listed

1,399

1,399

Facebook

Facebook

Likes

7,849,301

7,849,301

Followers

8,030,472

8,030,472

Talked About

376,825

376,825

Youtube

Youtube

Uploads

1,706

1,706

Subscribers

492,000

492,000

Video Views

115,458,425

115,458,425

The public exhibits high levels of trust in the military for its ubiquitous delivery of goods and services and its commitment to a national rather than a partisan political agenda. The EAF nonetheless defends an administration that has eliminated autonomous political forces and routinely intimidates social and professional associations. Military agencies, alongside the General Intelligence Directorate, seek to dominate public discourse, and have purchased or taken over a wide range of media production and distribution companies.

Nation Building and Citizenship

The EAF represents a broad swath of Egyptian society, with approximately one million personnel in active and reserve forces, but its social profile varies between the officer corps, enlisted personnel, and conscripts. The EAF represents much the same middle and lower middle classes as the state apparatus as a whole. Copts are underrepresented in senior officer ranks, but the EAF does not actively restrict their enrollment in military academies. In contrast, a formal vetting process blocks academy applicants with lower-income backgrounds or Islamist leanings, and enlisted personnel are barred from advancing to officer rank, reinforcing the class barrier.

Universal conscription contributes to the perception that the EAF is a nation-building institution that underpins citizenship and bridges gaps between social classes. Many families have members in the armed forces, either as career enlisted personnel or conscripts, and regard the EAF as belonging to them, although the movement of military officers from middle-class, inner city neighborhoods to suburbs and gated communities has weakened the perception of representativeness.

The legitimacy of the EAF’s role in society relies more on what it gives the public than on any perception of developing a rule-bound and legally compliant state. Poorer citizens value the subsidized commodities and services that the EAF provides, while middle-class citizens are more likely to focus on the EAF as a bulwark against domestic foes and the insecurity and violence affecting other Arab countries. The military also contrasts with civilian officials and representatives, whom the public often regards as corrupt, incompetent, and self-serving.

Communal identities do not shape military perceptions of society. The armed forces do not regard any particular community as a natural enemy of the state, although they may regard local populations in Sinai and in southern and western Egypt as outside the national ethnic mainstream and inculcate deep antagonism for the Muslim Brotherhood. The EAF is also reluctant to recruit and integrate women in the ranks, and female personnel are limited to clerical, medical, and media roles. Government and military promises to initiate policy and program planning on female integration have not been put into action.

In an effort to win hearts and minds among lower-income groups, the armed forces publicize their contribution to building public infrastructure and low-income housing construction, development projects in local communities, and food distribution to the needy. The military fills gaps in food supply by running bakeries and slaughterhouses and importing cheap poultry and meat in bulk. The EAF also provides reduced-price medical services to the public and participates in national public health campaigns.

The armed forces cultivate good will among the middle-class with reduced fees at military-run hotels, clubs, and resorts, as well as access to consumer goods and appliances at affordable prices. Military companies and agencies also run training programs in technical and administrative skills marketable in the public and private sectors, and the military invests in shaping public opinion with media content from the Department of Morale Affairs and its network of media companies.

Universal conscription contributes to the perception that the EAF is a nation-building institution that underpins citizenship and bridges gaps between social classes. Many families have members in the armed forces, either as career enlisted personnel or conscripts, and regard the EAF as belonging to them, although the movement of military officers from middle-class, inner city neighborhoods to suburbs and gated communities has weakened the perception of representativeness.

The legitimacy of the EAF’s role in society relies more on what it gives the public than on any perception of developing a rule-bound and legally compliant state. Poorer citizens value the subsidized commodities and services that the EAF provides, while middle-class citizens are more likely to focus on the EAF as a bulwark against domestic foes and the insecurity and violence affecting other Arab countries. The military also contrasts with civilian officials and representatives, whom the public often regards as corrupt, incompetent, and self-serving.

Communal identities do not shape military perceptions of society. The armed forces do not regard any particular community as a natural enemy of the state, although they may regard local populations in Sinai and in southern and western Egypt as outside the national ethnic mainstream and inculcate deep antagonism for the Muslim Brotherhood. The EAF is also reluctant to recruit and integrate women in the ranks, and female personnel are limited to clerical, medical, and media roles. Government and military promises to initiate policy and program planning on female integration have not been put into action.

In an effort to win hearts and minds among lower-income groups, the armed forces publicize their contribution to building public infrastructure and low-income housing construction, development projects in local communities, and food distribution to the needy. The military fills gaps in food supply by running bakeries and slaughterhouses and importing cheap poultry and meat in bulk. The EAF also provides reduced-price medical services to the public and participates in national public health campaigns.

The armed forces cultivate good will among the middle-class with reduced fees at military-run hotels, clubs, and resorts, as well as access to consumer goods and appliances at affordable prices. Military companies and agencies also run training programs in technical and administrative skills marketable in the public and private sectors, and the military invests in shaping public opinion with media content from the Department of Morale Affairs and its network of media companies.

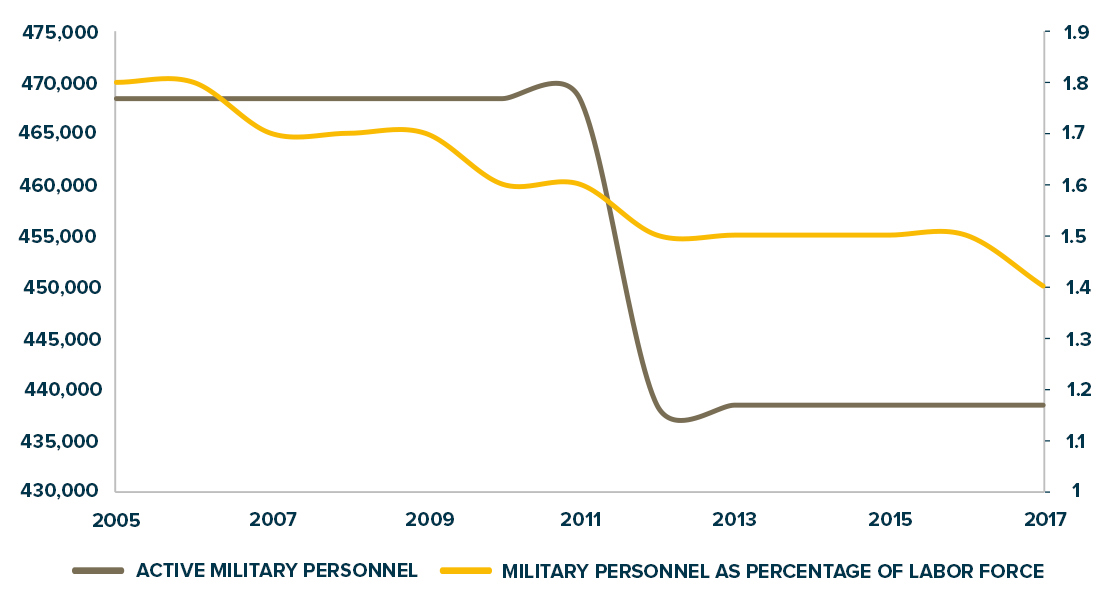

Active Military Personnel Versus Labor Force

Budget and Economy

Military Economy

The defense industry and other agencies belonging to the Ministry of Defense and the armed forces produce a wide range of goods and services for civilian use. These encompass public infrastructure and housing, household appliances and other consumer goods, industrial chemicals and components, vehicles, raw and processed minerals, and management services. The government presents military economic activity as contributing to national development, generating state revenue, breaking monopolies, and stabilizing prices in civilian markets.

The feasibility of military economic activity is questionable. Military agencies enjoy sweeping tax and customs exemptions, favorable exchange rates, and other subsidies, and retain all profits while transferring losses to the state treasury. Income is used to augment salaries, share dividends among senior officers, build military infrastructure, and purchase and maintain weapons that are not covered by U.S. military assistance. Exemption from financial oversight and audit makes it impossible to verify the cost-benefit of military delivery of public goods and services or how income is used.

The defense industry produces only vintage military technology and exports almost nothing, and its civilian production lines are mostly loss-making. All military companies and agencies depend on government contracts that are awarded on a non-competitive basis. Thousands of retired officers in public sector companies, general authorities, and local government steer contracts to military agencies, and President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi has also authorized them to form commercial companies to compete in civilian markets. Their expansion into real estate, commodities, and tourism is disrupting the private sector and crowding access to credit.

The feasibility of military economic activity is questionable. Military agencies enjoy sweeping tax and customs exemptions, favorable exchange rates, and other subsidies, and retain all profits while transferring losses to the state treasury. Income is used to augment salaries, share dividends among senior officers, build military infrastructure, and purchase and maintain weapons that are not covered by U.S. military assistance. Exemption from financial oversight and audit makes it impossible to verify the cost-benefit of military delivery of public goods and services or how income is used.

The defense industry produces only vintage military technology and exports almost nothing, and its civilian production lines are mostly loss-making. All military companies and agencies depend on government contracts that are awarded on a non-competitive basis. Thousands of retired officers in public sector companies, general authorities, and local government steer contracts to military agencies, and President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi has also authorized them to form commercial companies to compete in civilian markets. Their expansion into real estate, commodities, and tourism is disrupting the private sector and crowding access to credit.

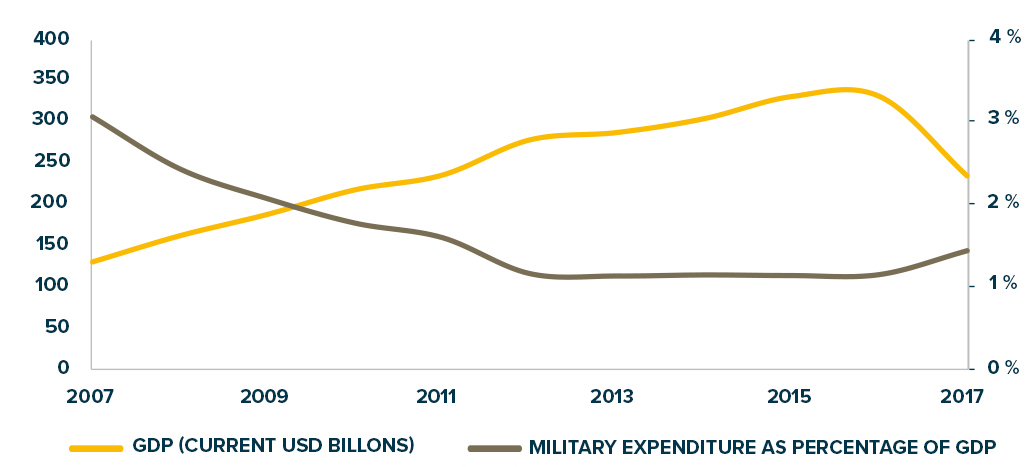

The defense budget is a modest percentage of gross domestic product and of general state budgets, but does not capture the full extent of defense funding and spending. Military businesses, public works contracts, investments, external assistance, and defense exports produce extra-budgetary income. The cost of purchasing new weapons systems seems to be covered by U.S. Foreign Military Financing, or loans from European banks that must be repaid, and it is not clear if the cost of training, maintenance, repair, and upgrades over the life of these systems is factored in.

The military passes investment costs and operating losses from its businesses to the public purse, and does not account for lost revenue due to the military’s tax and customs exemptions, favorable foreign exchange rates, and subsidized or free factors of production such as labor, energy, and water. The EAF also benefits from dual-use infrastructure built at public expense, and charges military pensions to the general state budget.

The Ministry of Defense and other military agencies retain incomes and budget surpluses in special discretionary funds, and only a special unit of the Ministry of Finance checks their books. Some seventy-four military-owned companies produce defense and civilian products and services with the same tax exemptions, subsidies, and protections as the rest of the military. Investment capital often appears to come from these special funds.

Public works dominate the military economy, especially the Armed Forces Engineering Authority, whose profit line has benefited from a surge in construction contracts since 2013. A portion of this income funds military perquisites and bonuses, and may pay for constructing military infrastructure, importing combat hardware, and maintaining equipment.

The military economy has contradictory effects. Pay, pensions, and procurement contribute to the national economy, and the construction of public infrastructure and housing generates jobs and adds value. But there is no evidence that military agencies are more efficient than private companies, and military-managed projects are plagued by delays, favoritism, and waste. They rely on noncompetitive contracting, crowd out civilian competitors, and impede innovation.

A very high risk of corruption is associated with potentially fraudulent contracts, illegal commission-taking, misuse of state assets, and extraction of illegal fees and bribes in return for licensing the use or rezoning of land controlled by the Ministry of Defense. The unofficial levying of fees and bribes for providing routine services appears to be common. The remit of the powerful Administrative Monitoring Authority does not extend to the military, and it is headed and almost entirely staffed by retired and active EAF officers.

National Defense

Imbalanced civil-military relations deprive the armed forces of the robust challenges that would help improve their capabilities and performance and evolve more effective responses to national security threats and challenges. This imbalance also removes incentives for internal accountability within the military, impeding the routine monitoring and evaluation that could lead to lesson learning and greater command initiative and operational autonomy. Resistance within the EAF to advice from foreign providers of military assistance also impedes upgrading skills and staying abreast of developments in global military affairs.

The EAF emphasizes procurement at the expense of acquiring genuine military strategic planning capacity, and displays limited ability to maintain, repair, and upgrade equipment and weapons systems. The decade-long failure to resolve a small-scale armed insurgency in North Sinai displays these shortcomings, but foreign officers responsible for bilateral military relationships with the EAF also assess that it would be incapable of conducting large-scale conventional operations.

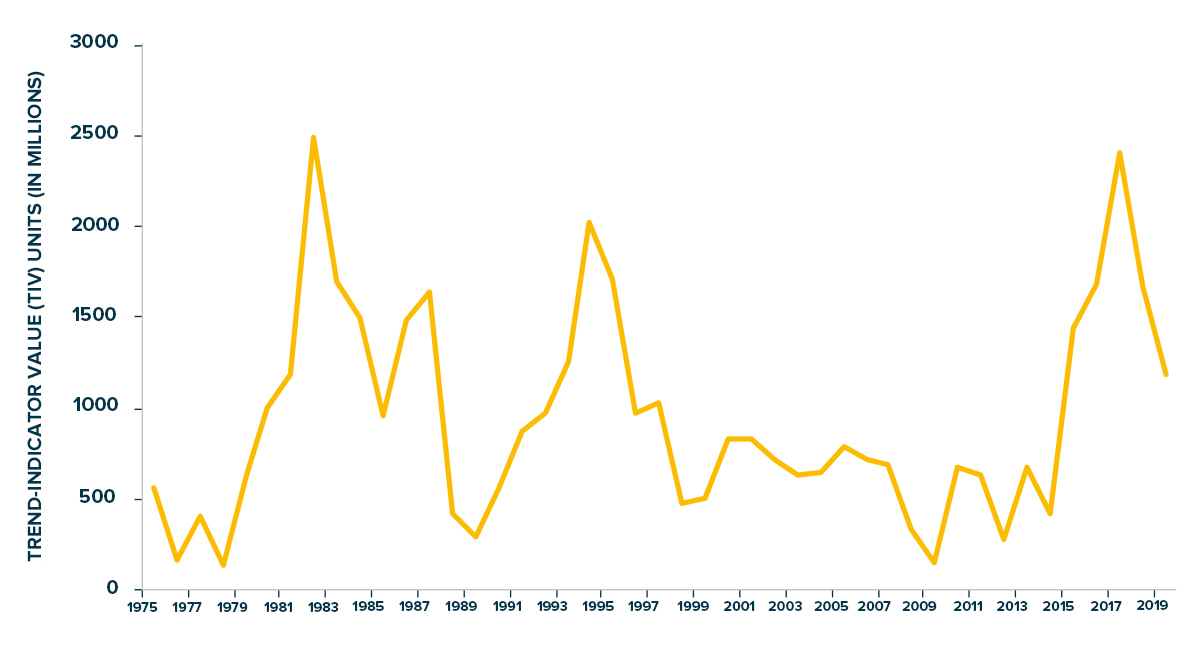

The armed forces receive sufficient funding and resources, whether from the state budget, foreign assistance, or military businesses. The Sisi administration has allocated significant political attention and material resources to developing military infrastructure and acquiring major combat systems. Arms worth approximately $8.8 billion were imported in 2014–2019, tripling the previous five-year amount and making Egypt the world’s third-largest arms importer.

The absence of a thorough national defense review process prevents Egypt from identifying military needs and measuring the utility of the EAF’s force structure, combat doctrine, and equipment. The opacity of defense funding and spending, coupled with a lack of civilian competence in defense affairs, further compounds the difficulty of monitoring and evaluating military cost-effectiveness. This applies to the local defense industry, as well, which produces only vintage-technology arms and munitions and lacks the capacity to develop technical adaptations and innovations to meet EAF needs.

The EAF often privileges political calculations and personal loyalties over competence in selecting officers for promotion or command appointments. This undermines military professionalism and the ability to deliver effective national defense outcomes. The emphasis on loyalty, obedience, and strict attachment to hierarchy discourage initiative and innovation, leaving the EAF unable to utilize the full potential of mid-level and junior officers and undervaluing its enlisted ranks.

Officer training focuses excessively on technical skills, military education is regarded more as a means to securing promotions and desk assignments than to developing command capacity, and exercises are highly choreographed, defeating their purpose of preparing for realistic combat conditions. Military rejection of any civilian involvement in defense affairs denies the EAF important capabilities, including data-based analysis and planning. Unwillingness to open up to scrutiny and change also bleeds into a reluctance to make effective use of the defense expertise that foreign providers of military assistance offer.

The EAF emphasizes procurement at the expense of acquiring genuine military strategic planning capacity, and displays limited ability to maintain, repair, and upgrade equipment and weapons systems. The decade-long failure to resolve a small-scale armed insurgency in North Sinai displays these shortcomings, but foreign officers responsible for bilateral military relationships with the EAF also assess that it would be incapable of conducting large-scale conventional operations.

The armed forces receive sufficient funding and resources, whether from the state budget, foreign assistance, or military businesses. The Sisi administration has allocated significant political attention and material resources to developing military infrastructure and acquiring major combat systems. Arms worth approximately $8.8 billion were imported in 2014–2019, tripling the previous five-year amount and making Egypt the world’s third-largest arms importer.

The absence of a thorough national defense review process prevents Egypt from identifying military needs and measuring the utility of the EAF’s force structure, combat doctrine, and equipment. The opacity of defense funding and spending, coupled with a lack of civilian competence in defense affairs, further compounds the difficulty of monitoring and evaluating military cost-effectiveness. This applies to the local defense industry, as well, which produces only vintage-technology arms and munitions and lacks the capacity to develop technical adaptations and innovations to meet EAF needs.

The EAF often privileges political calculations and personal loyalties over competence in selecting officers for promotion or command appointments. This undermines military professionalism and the ability to deliver effective national defense outcomes. The emphasis on loyalty, obedience, and strict attachment to hierarchy discourage initiative and innovation, leaving the EAF unable to utilize the full potential of mid-level and junior officers and undervaluing its enlisted ranks.

Officer training focuses excessively on technical skills, military education is regarded more as a means to securing promotions and desk assignments than to developing command capacity, and exercises are highly choreographed, defeating their purpose of preparing for realistic combat conditions. Military rejection of any civilian involvement in defense affairs denies the EAF important capabilities, including data-based analysis and planning. Unwillingness to open up to scrutiny and change also bleeds into a reluctance to make effective use of the defense expertise that foreign providers of military assistance offer.

Arms Imports

Note: The TIV is a unit of measure developed by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) to calculate the volume of international transfers of major conventional weapons. It does not represent actual prices and cannot be directly compared with figures for GDP or military spending.

Source: SIPRI